A resident of the all-Black town of Tullahassee, OK, and later a resident of the Black community of Reeves Addition in Muskogee, OK, Reverend William R. Purcells worked as a pastor, farmer, and organizer for the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. Like the majority of the members and organizers of the union, he is almost entirely unknown. In all of the books and articles written about the union, his name is mentioned once in an article on the Oklahoma Historical Society’s website. Hence, uncovering his life’s journey was itself a journey: a journey through archives, databases, and reels upon reels of microfilm; a journey to an abandoned church and cemetery; and a journey of meeting new people, anyone who might know something about this man.

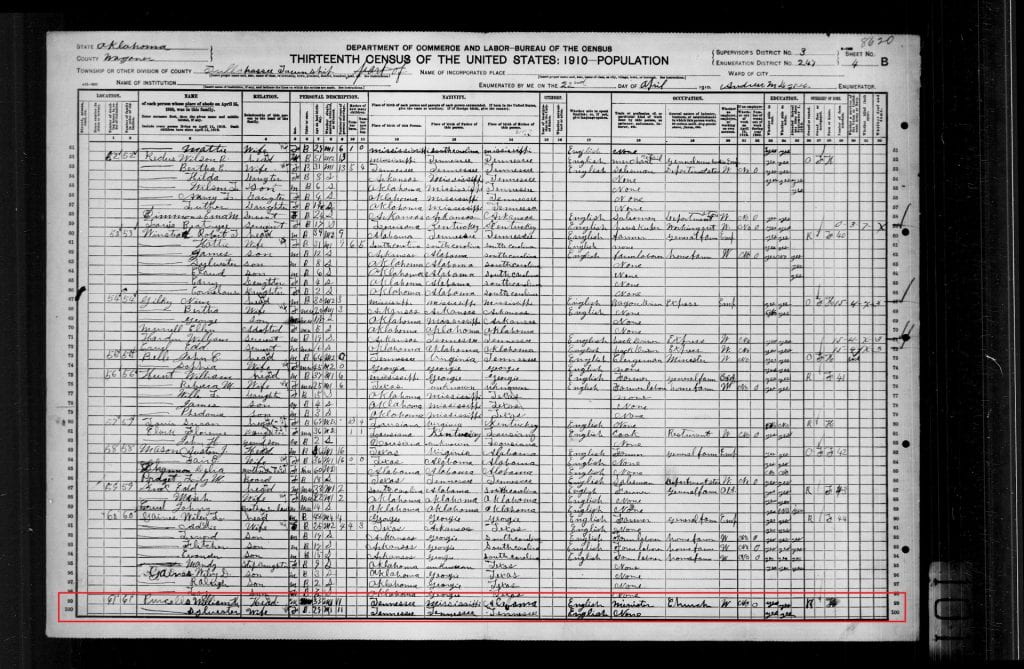

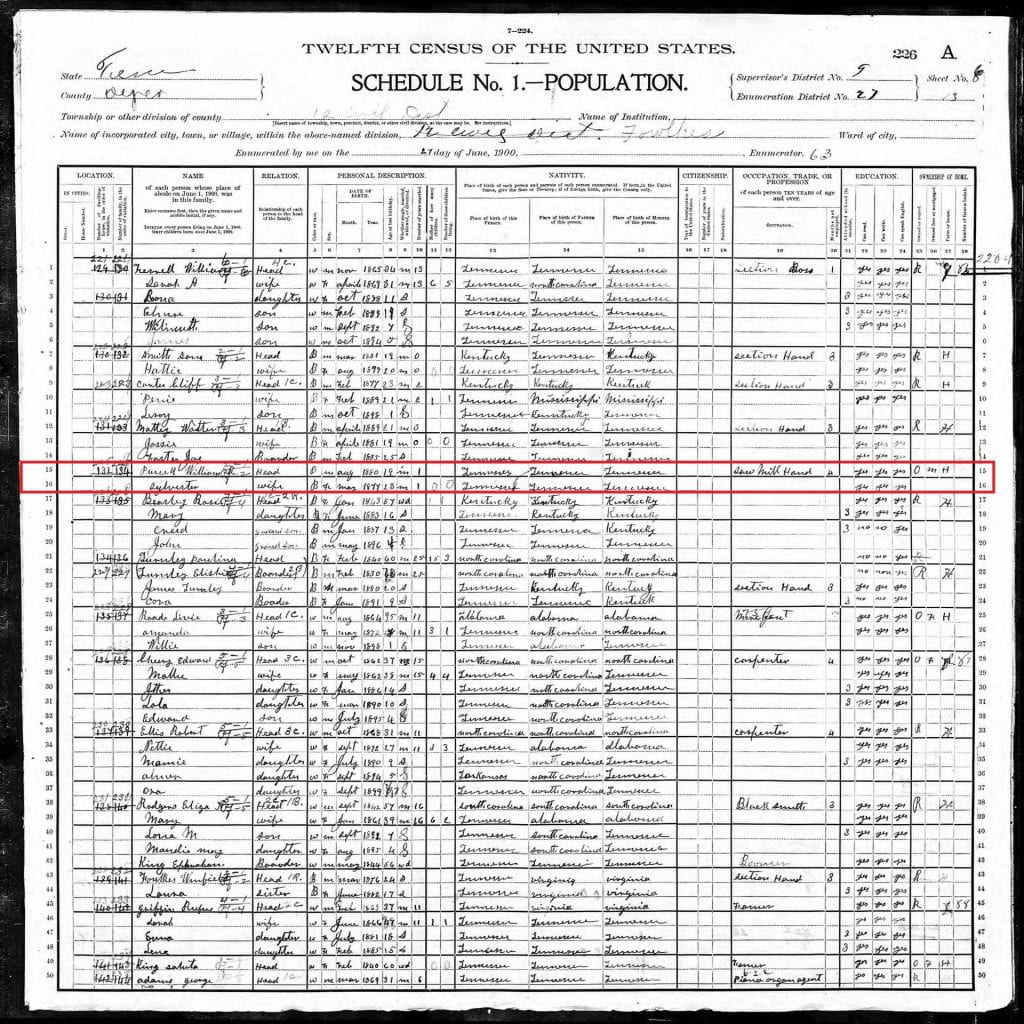

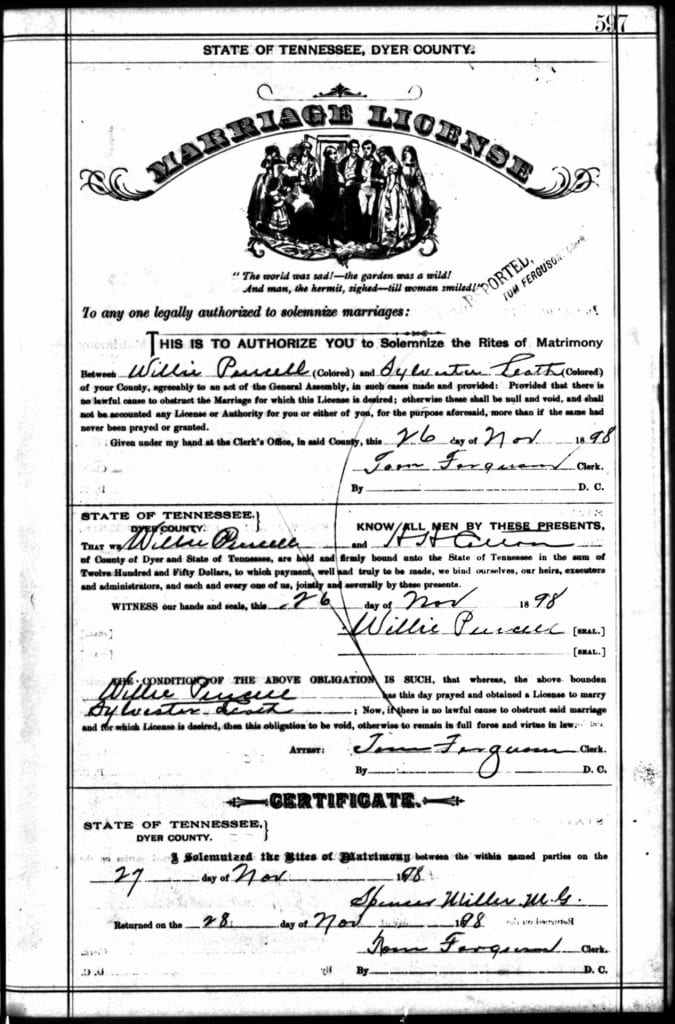

Long before he became known as Reverend, William R. Purcells lived in Dyer County, Tennessee, the state of his birth. Born to a father from Mississippi and a mother from Alabama around 1876, he was likely the child of formerly enslaved African-Americans. The young Willie Purcells married Sylvester Leath on November 28, 1898 in Dyer County where he worked as a sawmill hand. At some point between 1900 and 1910, the couple decided to move to Oklahoma.

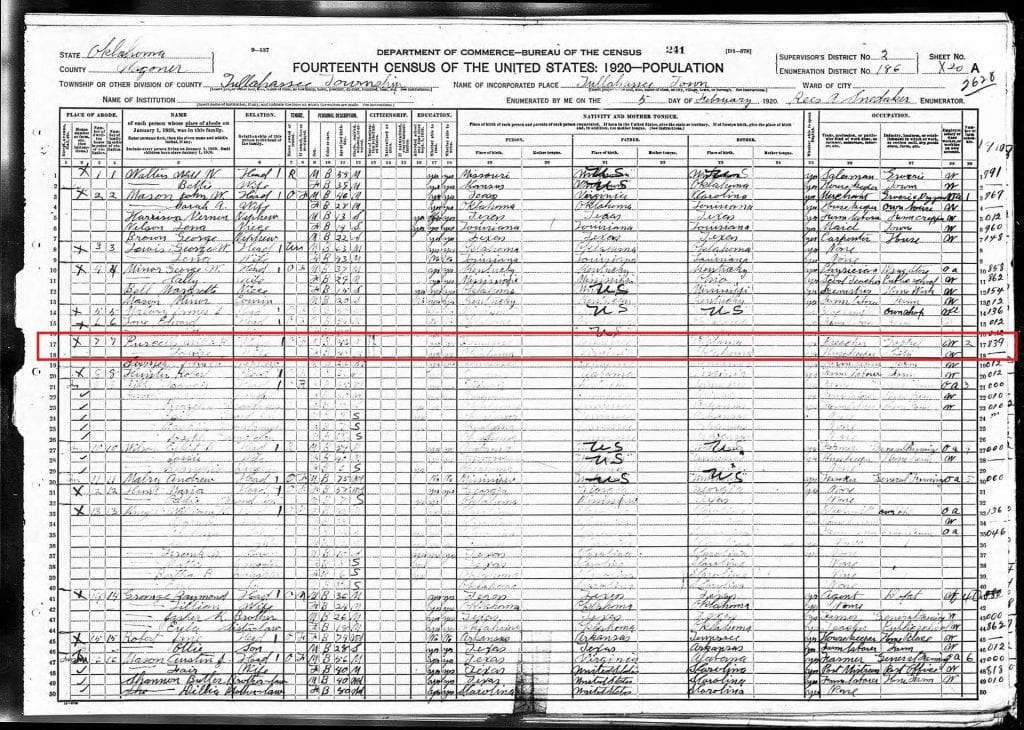

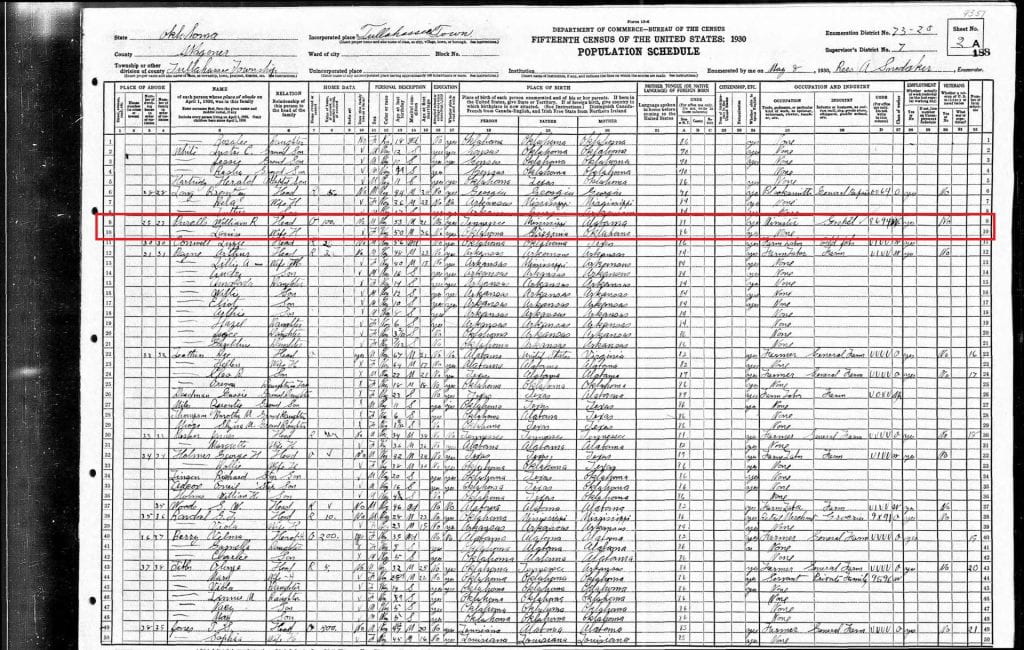

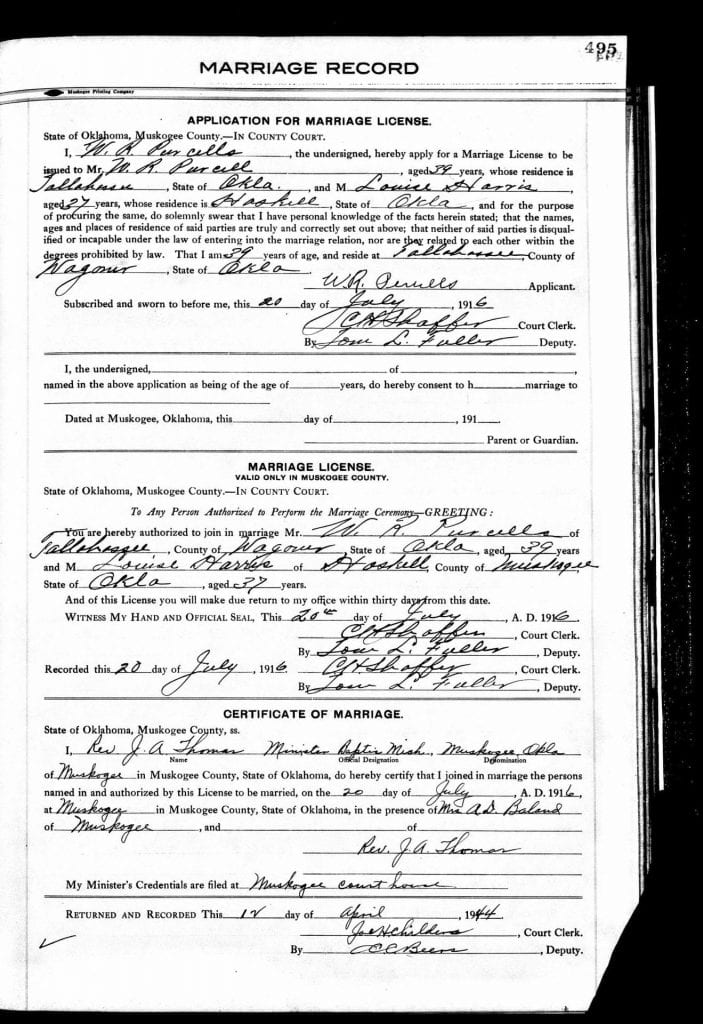

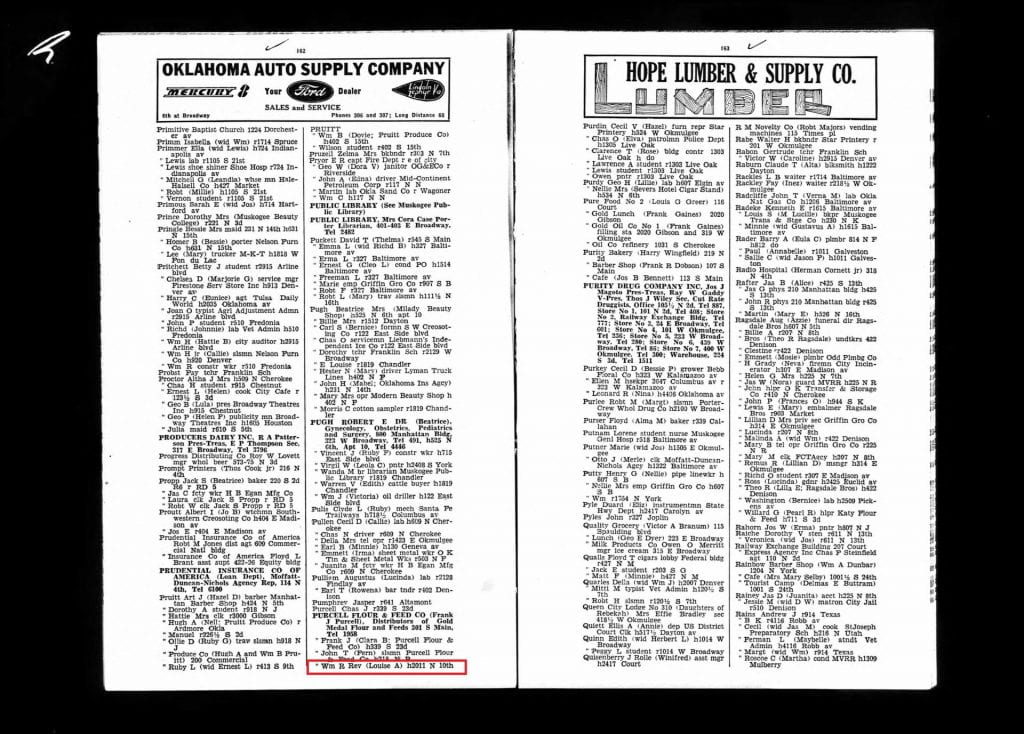

Willie and Sylvester moved to the all-Black community of Tullahassee, a former Creek Nation town that had been left to Creek freedpeople after the Tullahassee Manual Labor School burned down in 1880. In Tullahassee he became a pastor at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, one of the oldest churches in the state. Like many rural Black pastors during this period, he probably worked as a farmer as well. Tragedy struck when in 1916 his wife, Sylvester, passed away. Later the same year, he married Louise A. Harris from Haskell, Oklahoma. Census records indicate that he came into ownership of a piece of property by 1920 where his nephew from Tennessee, John C. Sawyers, lived with them for a time.

During this period in the 1910s and 1920s, Rev. Purcells likely became involved with Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. The all-Black towns of Oklahoma became bastions of support for the UNIA, and almost all of them hosted UNIA divisions, including Tullahassee. Garveyites in the rural south were primarily men, sometimes women, usually thirty-five years of age or older, married, literate, Cotton Belt tenant farmers, sharecroppers, teachers, and preachers. Additionally, there were several Garveyites who became involved with the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, including the union’s first vice-president, E. B. McKinney. Lastly, Rev. Purcells preached at both Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal churches during his life, the two denominations most closely associated with the UNIA. Thus Rev. Purcells fits the profile perfectly. Perhaps the UNIA Papers or the UNIA Records Collection may be able to shed some light on this matter. Regardless, he was a man of profound faith, with a strong connection to his community.

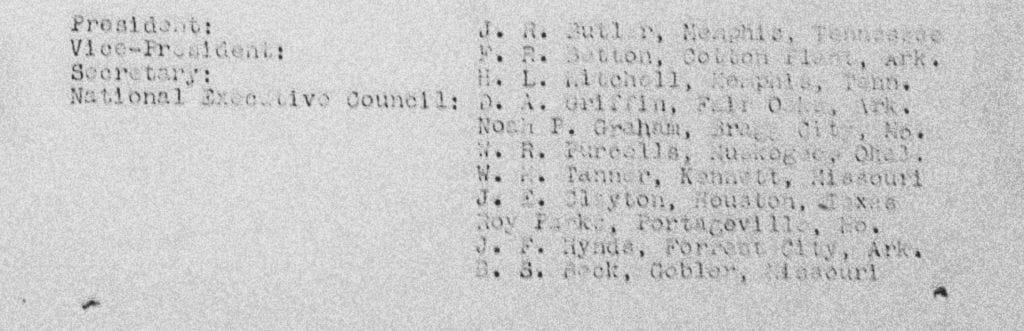

A list of the officers elected during the Seventh Annual Convention in 1941. From the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Papers, Reel 60.

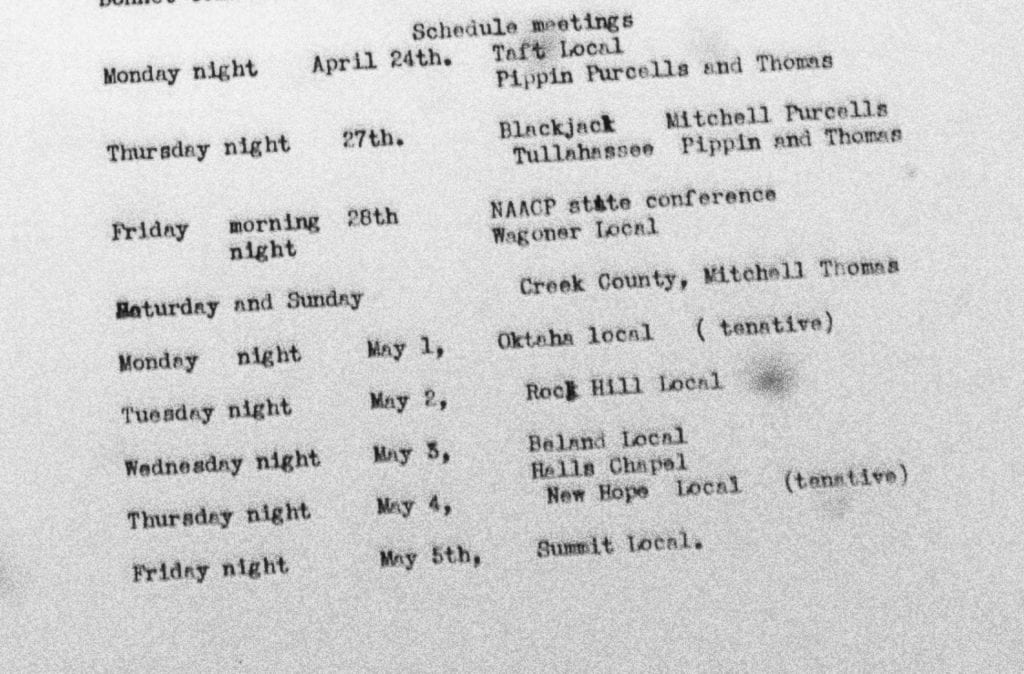

An list of meetings in Oklahoma during the reorganization of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union in 1939. From the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Papers, Reel 11.

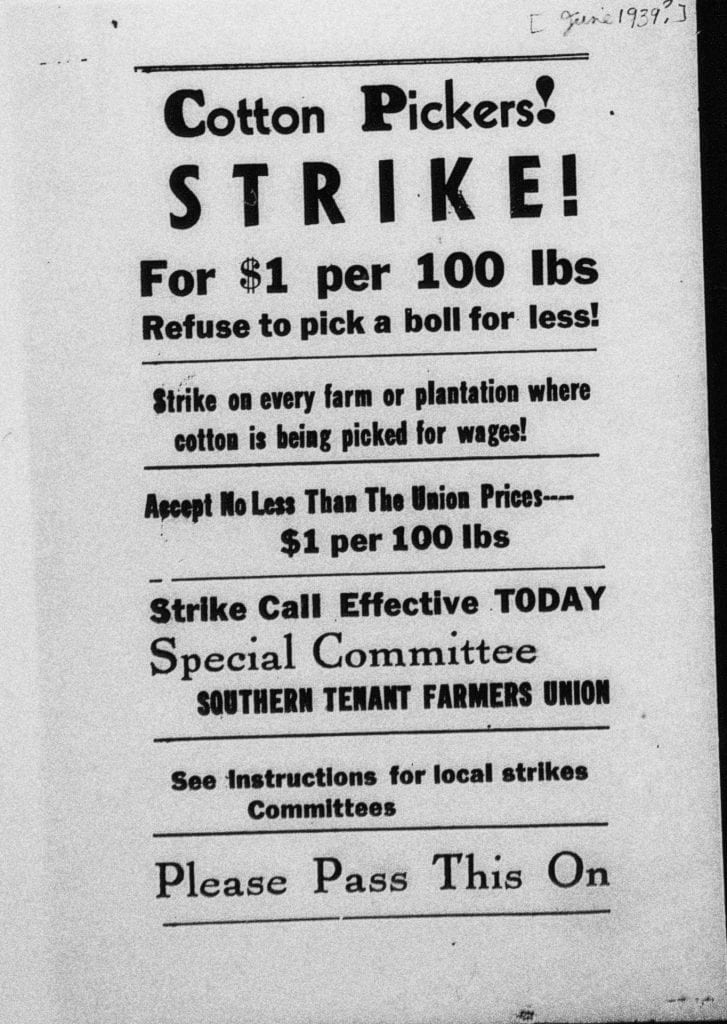

A strike flier. From the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Papers, Reel 11.

One of many letters written by Rev. Purcells to the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union headquarters in Memphis, TN. From the Southern Tenant Farmers Union Papers, Reel 12.

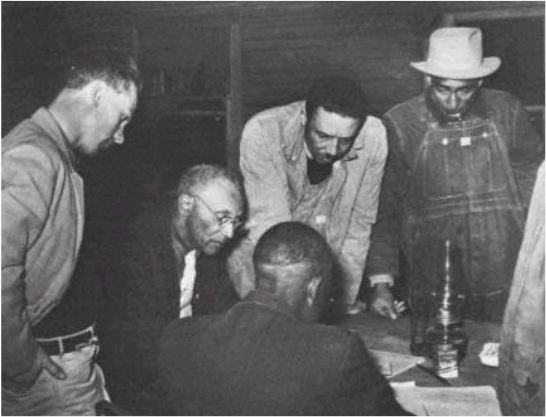

Black farmers organizing a tenants’ union, circa 1935. From Journey Towards Hope by Jimmie Lewis Franklin.

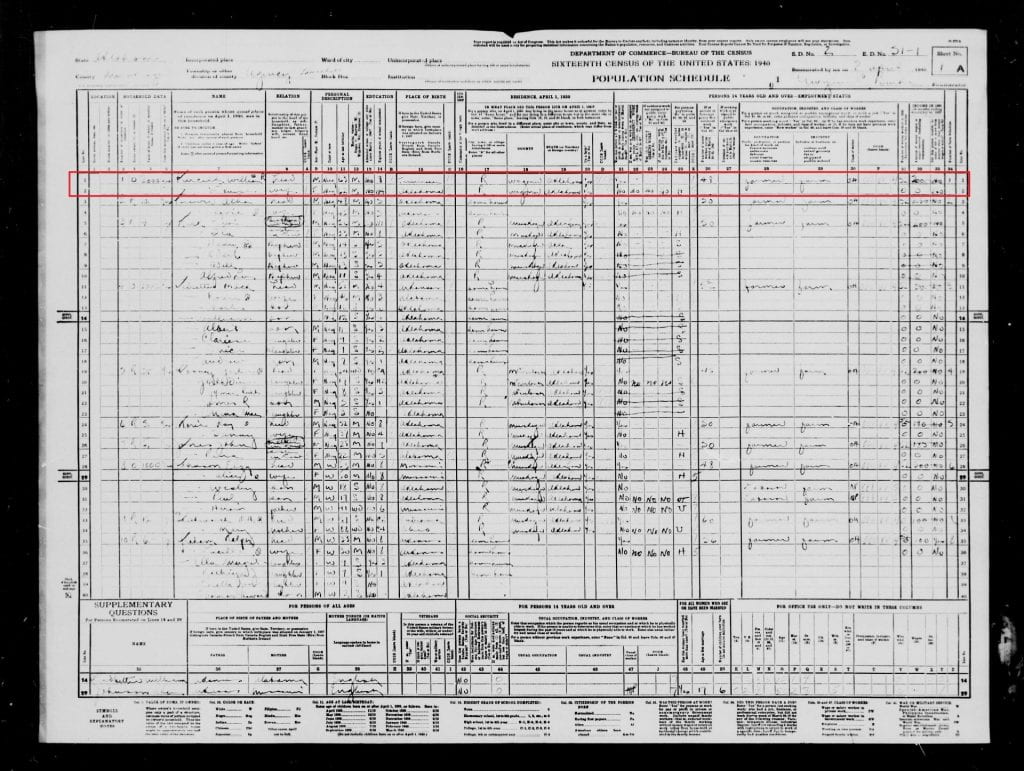

During the 1930s, Rev. W. R. Purcells joined the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Founded in Tyronza, AR in 1934, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union organized sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and day laborers into a single union in order to struggle against the tyranny of the planter class. While many unions have a marked history of segregation, from the beginning the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union organized African-Americans, Native Americans, whites, and Mexican-Americans because, in the words of Ike Shaw, a survivor of the Elaine Massacres, “the same chain that holds my people holds your people too.” Although the union was primarily led by white socialists, their power came from the courageous involvement of thousands upon thousands of landless Black farmers, who comprised anywhere from one-half to three-fourths of the membership. The Southern Tenants Farmers’ Union was a preaching and singing movement, where Black oral traditions of poetry and song were part of daily life in the union and functioned to bridge racial and class divides, building solidarity and group action through mass singing. Black community networks, like those to which Rev. Purcells was so intimately connected, served an essential role in organizing new union locals, and Black churches provided most meeting places. After a sectarian dispute between socialists and communists split the union, Rev. Purcells played a crucial role in reorganizing union locals in Oklahoma. He worked as the state secretary for the union in Oklahoma, was an elected officer of the National Executive Council, and even spoke at NAACP meetings in Oklahoma. The union could not function without organizers like Rev. Purcells.

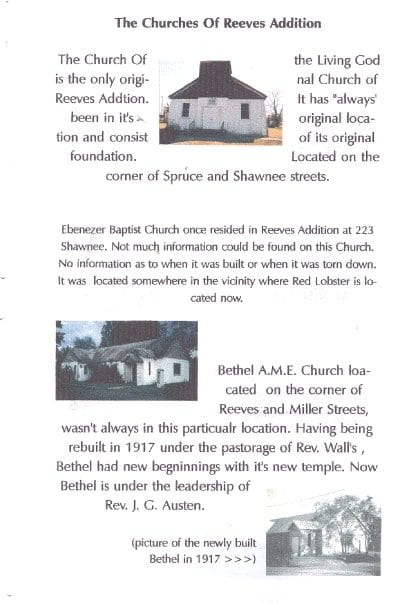

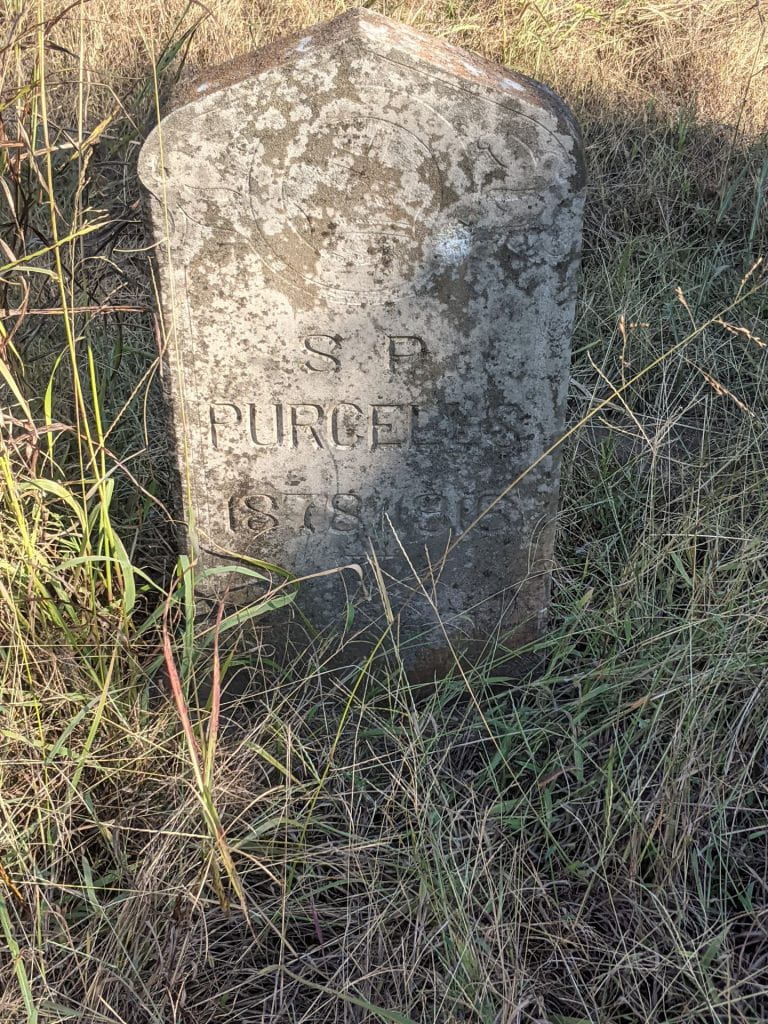

In 1940, William and Louise moved to a home in the Black community of Reeves Addition in Muskogee, OK. According to Sammie Stanford, a former resident of Reeves Addition, Rev. Purcells preached at Bethel A.M.E. Church there in addition to Pleasant Grove Baptist Church. He lived in Reeves Addition with his wife until his passing in 1950. He lies buried next to his first wife in Pleasant Grove Cemetery. While he had no children, Rev. William R. Purcells left behind a legacy of faith, community, and struggle.

The headstone of Rev. William R. Purcells. Picture by author.

The headstone of Sylvester P. Purcells. Picture by author.

Main Sources

– The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Papers on microfilm

– Census Records, Marriage Records, Etc.

Further Reading

On the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union:

– Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal by Donald Grubbs

– The Forgotten Farmers: The Story of Sharecroppers in the New Deal by David Eugene Conrad

– The Gospel of the Working Class: Labor’s Southern Prophets in New Deal America by Erik S. Gellman and Jarod Roll

– Mean Things Happening in this Land by H. L. Mitchell

– Sharecropper’s Troubador: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and the African American Song Tradition by Michael K. Honey

On Rural Garveyism:

– Grassroots Garveyism: The Universal Negro Improvement Association in the Rural South, 1920-1927 by Mary G. Rolinson